This is an old revision of the document!

Copellia

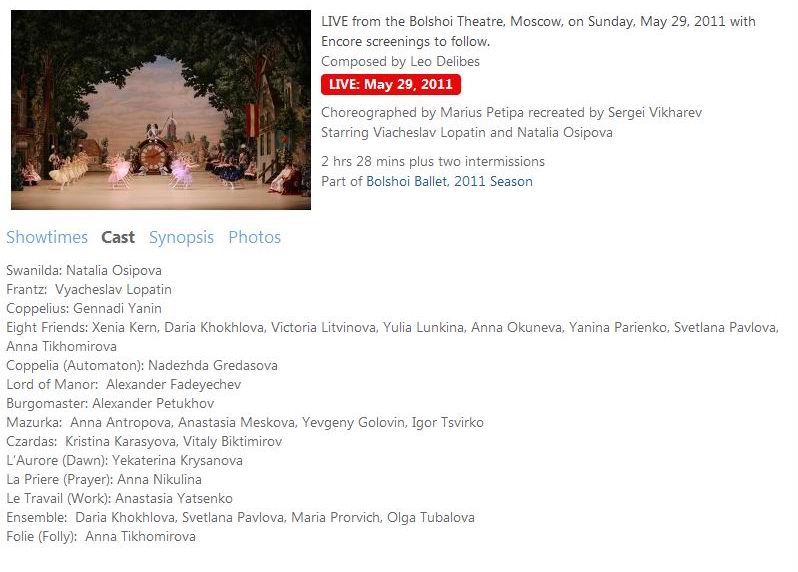

Wow, one of the best Copellia's I have seen. A huge cast, Libbie said she counted 48 dancers on stage. High energy and even higher kicks by the principals make this a very memorable performance.

==== Review by the Royal Ballet ====

The Bolshoi's new production of Coppélia could have been staged entirely for the benefit of Natalia Osipova. Dancing Swanilda, the ballet's flirty, feisty heroine, she gets to show off her unique and astonishing range – from snub-nosed ingenue to grand ballerina, with all shades of spinning virtuosity and cute mischief in between.

Even in stillness, Osipova looks more alive than anyone else on stage. Her wide, challenging eyes, enormous grin and mockingly angled brows are already telling Swanilda's story before she has begun to move. Once she's dancing, you don't look at anyone else.

Technically, there is little Osipova can't do. Her sharp, flexible little feet make flashing stitchwork out of Swanilda's tiniest steps and jumps; her arms make floating music with the score. When she's throwing out big, fast développés – her legs unfurling high in the air – she's calmly lifting up her petticoats and smiling with glee. And she's still scattering treats and surprises all through the third act, adding a whirling flourish of fouettés and leaping halfway across the stage to be caught in Franz's final embrace.

This new Coppélia, staged by Sergei Vikharev, has gone all the way back to the Cecchetti-Petipa production of 1894. The Royal Ballet's version uses the same text, but readings vary, and the Bolshoi's Coppélia is on a much more opulent scale than the Royal's.

In the first act, for instance, the Mazurka and Czardas are not spontaneous, villagey affairs, but grand divertissements, the stage packed with stamping, heel-clicking dancers. In the wedding festivities of the third act, where Swanilda and her straying fiance Franz are finally united, the delicately symbolic variations – Dawn, Prayer etc – are vamped into an elaborate allegorical interlude, complete with full corps de ballet and a giant clock presided over by an angel and cherubs.

This may well be a more authentic reading of the ballet, but it brings with it a different mode of storytelling and character. Coppélius is presented as a generic boffin, lacking the eccentricity, loneliness and bitterness that, in the Royal's production, make him so odd and scary. And while Ruslan Skvortsov dances an appealing Franz, the Bolshoi's acting style makes his spats with Swanilda and his skirt-chasing follies a little less funny than they should be.

There is no definitive Coppélia, however; every new staging adds a new slant. And the Bolshoi's is everything you would want it to be: very big, very Russian and danced to the hilt.